Goal Exploration Processes

Autotelic agents—agents that are intrinsically motivated to represent, generate and pursue their own goals—aim at growing their repertoire of skills. This implies that they need not only to discover as many goals as possible, but also to learn to achieve each of these goals. When these agents evolve in environments where they have no clue about which goals they can physically reach in the first place, it becomes challenging to handle the exploration-exploitation dilemma.

The standard Reinforcement Learning (RL) setup is not suitable for training artificial agents to achieve a set of different goals, since there is usually a unique mapping between a goal and a reward signal. A straightforward way to circumvent this issue is to define goal experts modules. This implies that an embodied agent would have a set of policies equal to the number of potentially learnable goals. Whenever the agent attempts to reach a particular goal, it selects actions according to the policy that corresponds to this goal. These methods defined the first attempts to solve multi-goal problems [Kaelbling 1993; Baranes and Oudeyer 2013], some of which used modular representations of the state space [Forestier and Oudeyer 2016]. Unfortunately, all these methods present two main drawbacks. First, they all require knowing the number of goals beforehand in order to define the number of policies to be trained. Second, they do not leverage generalization and transfer between goals, since all the policies are by definition independent from one another.

Recently, with the promising results leveraged by neural networks as universal function approximators, a new framework where a single policy could learn to achieve multiple goals has been developed. This defines the sub-family of Goal-Conditioned Reinforcement Learning (GCRL), which originated from results on universal value function approximators [Schaul et al. 2015]. The main principle is simply to condition the agent’s policy not only on observations or states, but also on embeddings of the goals to be achieved. Instead of having one policy for each goal, these methods have a single contextual policy, where the context defines the goal [Andrychowicz et al. 2017; Colas et al. 2019; Akakzia et al. 2021].

Formalizing Multi-Goal Reinforcement Learning Problems

We propose to formalize multi-goal reinforcement learning problems. While standard RL uses a single Markov Decision Process (MDP) and requires the agent to finish one specific task defined by the reward function, GCRL focuses on a more general and more complex scenario where agents can fulfill multiple tasks simultaneously. To tackle such a challenge, we introduce a goal space \(\mathcal{G}~=~Z_{\mathcal{G}} \times R_{\mathcal{G}}\), where \(Z_{\mathcal{G}}\) denotes the space of goal embeddings and \(R_{\mathcal{G}}\) is the space of the corresponding reward functions. We also introduce a tractable mapping function \(\phi~:~\mathcal{S} \rightarrow Z_{\mathcal{G}}\) that maps the state to a specific goal embedding. The term goal should be differentiated from the term task, which refers to a particular MDP instance. Next, we need to differentiate the notions of desired goal and achieved goal.

-

Achieved Goal: An achieved goal defines the outcome of the actions conducted by the agent during a rollout episode. More specifically, it is the output of the mapping function applied at time step \(t\) on the current state of the agent: \(\phi(s_t)\). We denote by \(p^a_\mathcal{G}\) the distribution of achieved goals. Note that these goals are exactly the goals discovered by the agent in play.

-

Desired Goal: A desired goal defines the task that the agent attempts to solve. It can be either provided externally (by a simulator or an external instructing program) or generated intrinsically. We denote by \(p^d_{\mathcal{G}}\) the distribution of desired goals. This distribution is predefined when the agent receives goals from its external world, and corresponds to the distribution of achieved goals if the agent is intrinsically motivated.

Based on these definitions, we extend RL problems to handle multiple goals by defining an augmented MDP \(\mathcal{M} = \{\mathcal{S}, \mathcal{A}, \mathcal{T}, \rho_0, \mathcal{G}, p^d_{\mathcal{G}}, \phi\}\). Consequently, the objective of \gcrl is to learn a goal-conditioned policy \(\pi~:~\mathcal{S} \times \mathcal{A} \times \mathcal{G} \rightarrow [0, 1]\) that maximizes the expectation of the cumulative reward over the distribution of desired goals:

\[\pi^* = \textrm{arg}\max_{\pi} ~ \mathbb{E}_{\substack{g\sim p^d_{\mathcal{G}} \textrm{, } s_0\sim \rho_0 \\ a_t\sim \pi(.~|~s_t, g) \\ s_{t+1}\sim \mathcal{T}(s_t,a_t)}} \Big[\sum_t \gamma^t R_{\mathcal{G}} (\phi(s_{t+1})~|~z_g) \Big].\]Goal Exploration Processes

In multi-goal setups, the objective of goal-conditioned artificial agents is to simultaneously learn as many goals as possible. In other words, the training of such agents should in principle yield optimal goal-conditioned policies that maximize the coverage of the goal space. This coverage is usually defined with reference to the distribution of desired goals. Hence, agents should be able to efficiently explore their behavioral goal space in order to match the widest possible distribution of desired goals. Goal Exploration Processes (GEPs) are a family of frameworks for exploring multiple goals. For any environment—which can be defined by a state space \(\mathcal{S}\), an action space \(\mathcal{A}\) and a transition distribution \(\mathcal{T}\) that determines the next state given a current state and an action—a GEP essentially aims at maximizing its behavioral diversity by exploring the maximum number of goals. We consider goals here as pairs composed of a fitness function and a goal embedding, where the latter is the result of projecting the state space on a predefined or learned goal space \(\mathcal{G}\) using a surjective function: each goal is mapped to at least one state.

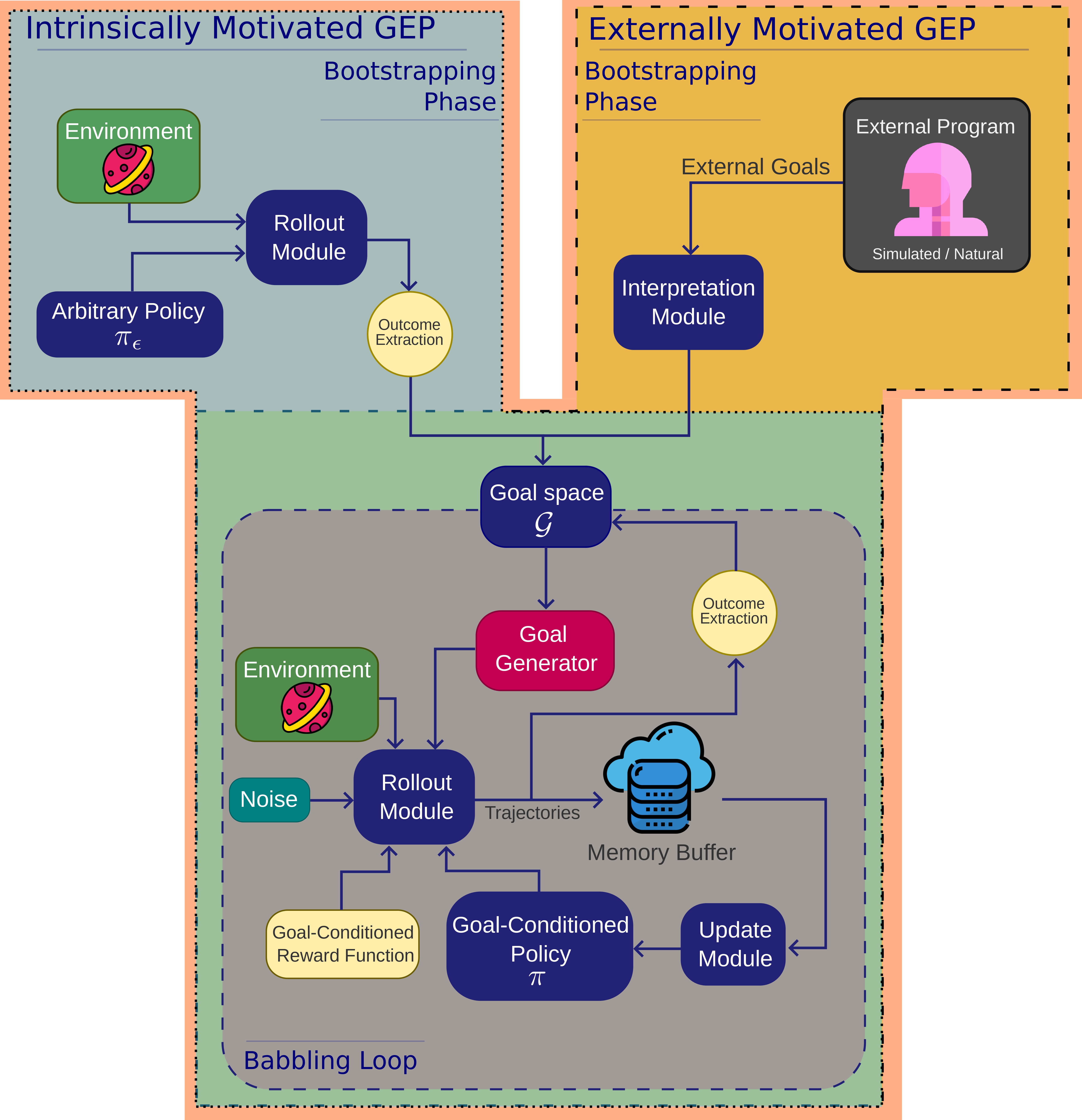

GEPs were first defined in the context of intrinsically motivated population based agents [Forestier et al. 2017]. In this part, we present GEPs as a general framework regardless of the underlying motivations (which can either be external or internal). First, we start from the policy search view on GEPs to derive a policy gradient perspective for goal-conditioned RL agents (See Figure 1 for an illustration). Then, depending on the source of motivations, we present the sub-families: Externally Motivated and Internally Motivated GEPs.

Fig.1-Illustration of the two stages leveraged by the Goal Exploration Processes (GEPs), as seen from the policy search perspective (left) and the goal-conditioned \rlearning perspective (right).

GEPs: Policy Search Perspective

From the policy search point of view, GEPs explore multiple goals starting from an initial population of policy parameters. The process leverages two phases: a first phase called the bootstrapping phase, which is conducted once, and a second phase called the search loop, which is repeated until convergence. Both phases require an outcome extractor, which is a predefined deterministic function that takes as input the policy parameters and outputs the outcome of applying that particular policy in the environment.

Concerning the bootstrapping phase, \(N\) sets of policy parameters are randomly sampled from \(\Theta\). Each one of the sampled policies is fed the outcome extractor to observe the corresponding outcome, which lays in an outcome space \(\mathcal{O}\). The pair formed by each policy and the corresponding outcome is stored in a buffer defining the population where the search phase will be conducted.

Concerning the search loop, the following cycle is repeated until convergence. First, a set of outcomes is sampled from the outcome space \(\mathcal{O}\). Second, this sampled outcomes are fed to the search module which looks in the available population for the closest policy parameters that achieve the sampled outcomes (simply using the \(K\)-nearest neighbors algorithm for instance). Third, a noise is applied to the policy parameters picked from the previous step. This promotes behavioral diversity and enables the potential discovery of new outcomes. In fact, the noisy policy parameters are fed to the outcome extractor, yielding an outcome for each entry. Finally, the obtained outcomes are appended to the initial outcome space \(\mathcal{O}\), while the pairs of policy parameters and the corresponding outcomes are added to the initial population.

GEPs: Policy Gradient Perspective

While the objective of GEPs from the policy search perspective is to maximize the size of the explored population of \(<policy, outcome>\) pairs, the policy gradient view presents it differently. In this perspective, the output of the process can be a single policy and a set of goals that the policy can achieve. In the policy gradient perspective, the policy is conditioned on the goals. The process leverages two phases: first a bootstrapping phase to initialize the goal space, then a babbling loop to learn and discover new goals.

During the bootstrapping phase, the goal space \(\mathcal{G}\) is filled with either a set of arbitrarily discovered or externally predefined goals, depending on the nature of motivations considered within the process.

During the babbling loop, the following cycle is repeated until convergence. First, a goal generator is used to sample goals from the goal space \(\mathcal{G}\). Second, a rollout module takes as input the sampled goals, the environment, a goal-conditioned reward function, a goal conditioned policy and noise to produce trajectories. This rollout module can be viewed as running an episode within a simulator using an arbitrary policy with predefined noise. Third, the obtained trajectories are stored in a memory buffer, which feeds an update module responsible for adjusting the goal-conditioned policy so that it maximizes the reward. Finally, the new trajectories are used to extract novel goals discovered during play. These goals are added to the initial goal space.

In the remainder of the document, we adopt the policy gradient perspective. Depending on the origins of goals obtained in the bootstrapping phase, we consider two sub-families of GEPs: externally and internally motivated.

Externally Motivated Goal Exploration Processes

Externally Motivated Goal Exploration Processes (EMGEPs) is a sub-family of GEPs where goals are predefined externally. Recall that a goal is a pair of a goal achievement function and a goal embedding. During the bootstrapping phase, an external program defines the goals that will be babbled and the corresponding goal achievement functions. If goals are discrete, then all goals are given. If goals are continuous, then both the support and the goal generator are given. See Figure 2 for an illustration.

If the goal generation process is embedded within the simulator and not the agent, then the corresponding GEP is considered as an EMGEP. Standard works that tackle the multi-goal reinforcement problem usually define a goal generation function within the environment [Schaul et al. 2015; Andrychowicz et al. 2017; Lanier et al. 2019; Li et al. 2019]. If goals are given by an external program, such as an external artificial or human agent, the corresponding GEP is also considered as an EMGEP. In particular, instruction following agents are the most straightforward EMGEPs, where agents are fully dependent on external goals in the form of natural language instructions [Hermann et al. 2017; Bahdanau et al. 2018; Chan et al. 2019; Cideron et al. 2019; Jiang et al. 2019; Fu et al. 2019].

Intrinsically Motivated Goal Exploration Processes

Intrinsically Motivated Goal Exploration Processes (IMGEPs) is a sub-family of GEPs where goals are exclusively discovered by the exploring agents itself. In other words, there is no external signal to provide goal embeddings nor goal achievement functions. Initially, during the bootstrapping phase, IMGEP agents have no clue whatsoever on the goal space. They use an arbitrary policy performing random actions in the environment and unlocks easy goals that are close in distribution term to the distributions of initial states. Once a sufficient set of goals is discovered, the babbling phase kicks off. As opposed to the first phase, the babbling phase uses a goal-conditioned policy. The exploration-exploitation dilemma is stronger in IMGEPs: the exploration should be efficient enough to avoid getting stuck in a particular distribution of discovered goals, but should be smooth enough to avoid catastrophic forgetting or getting the policy stuck in a local minimum.

For IMGEPs, the goal generation process is inherent to the agent. It is the agent itself that discovers the goals that it learns about (that is, it discovers both goal embeddings and goal achievement functions). Note that IMGEPs can discover a goal space whose support is defined externally (example: 3D positions, relational predicatess) [Nair et al. 2018; Colas et al. 2019; Colas et al. 2020; Akakzia et al. 2021; Akakzia and Sigaud 2022], or a goal space that is previously learned in an unsupervised fashion, using information theory techniques for example [Warde-Farley et al. 2018], see Figure 2 for an illustration.

Fig.2-Illustration of the two sub-families of Goal Exploration Processes (GEPs): (left) IMGEPs (right) EMGEPs. Each type has its own bootstrapping phase but both share the same babbling loop.

Autotelic Reinforcement Learning

The term autotelic was first introduced by the humanistic psychologist Mihaly Csikszenmihaly as part of his theory of flow. The latter corresponds to a mental state within which embodied agents are deeply involved in some complex activity without external rewarding signals [Mihaly 2000]. His observations was based on studying painters, rock climbers and other persons who show full enjoyment in the process of their activity without direct compensation. He refers at these activites as ``autotelic”, which implies that the motivating purposes (telos) come from the embodied agents themselves (auto).

In Artificial Intelligence, the term is used to define artificial agents that are self-motivated, self-organized and self-developing [Steels 2004; Colas et al. 2022]. More formally, autotelic agents are intrinsically motivated to represent, generate, pursue and learn about their own goals [Colas et al. 2022]. In the context of goal exploration processes, these agents are IMGEPs endowed with an internal goal generator: the goals that are explored and learned about depend only on the agents themselves.

In this part, we present an overview on recent autotelic reinforcement learning—autotelic agents trained with RL algorithms. We distinguish three categories, depending on whether the goal space and the set of reachable goals is known in advance. First, we present the case where autotelic agents do not know the goal space representation, but need to learn it themselves in an unsupervised fashion. Second, we present the case where autotelic agents know the goal space representation beforehand, but have no clue on which goals they can physically reach. Finally, we present the case where autotelic agents know both the goal space representation and the set of reachable goals, but need to self-organize their learning in order to master these goals.

Autotelic Learning of Goal Representations

When the structure of the goal space is not known in advance, artificial agents need to autonomously learn good representations by themselves. They usually rely on information theory methods which leverage quantities such as entropy measures and mutual information [Eysenbach et al. 2018; Pong et al. 2019]. The main idea is to efficiently explore their state space and extract interesting features that enable them to discover new skills, which they attempt to master afterwards. They use generative models such as variational auto-encoders [Kingma et al. 2019] to embed high-dimensional states into compact latent codes [Laversanne-Finot et al. 2018; Nair et al. 2018; Nair et al. 2019]. The underlying latent space forms the goal space, and generating a latent vector from these generative models corresponds to generating a goal from the goal space. While these approaches are task-agnostic, they usually do not leverage a sufficiently high level of abstraction. In fact, since states are usually continuous, distinguishing two different high level features corresponding to two close states is challenging (e.g. distinguishing when two blocks are close to each other without further information). Besides, the learned goal representation is usually tied to the training-set distribution, and thus cannot generate well to new situations.

Autotelic Discovery of Goals

When artificial agents know the structure of the goal space but have no clue about the goals that can be physically reached within this space, they need to efficiently explore and discover skills by themselves [Ecoffet et al. 2019; Pitis et al. 2020; Colas et al. 2020; Akakzia et al. 2021; Akakzia and Sigaud 2022]. Such scenarios become more challenging if randomly generated goals are likely to be physically unfeasible [Akakzia et al. 2021; Akakzia and Sigaud 2022]. In this case, the only goals that the agents can learn about are the ones that they have discovered through random exploration. Consequently, such agents need to have efficient exploration mechanisms that overcome bottlenecks and explore sparsely visited regions of their goal space. They might also need additional features such as the ability to imagine new goals based on previous ones [Colas et al. 2020], or to start exploring from specific states that maximize the discovery of new goals [Ecoffet et al. 2019; Pitis et al. 2020; Akakzia et al. 2021].

Autotelic Mastery of Goals

In some scenarios, artificial agents can know the structure of their goal space as well as the set of goals they can physically achieve. In other words, any goal they sample using their goal generator can potentially be reached and mastered. The main challenge for these agents is not to discover new goals, but rather to autonomously organize their training goals in order to master as many skills as possible. This is actually challenging, especially in environments where goals are of different complexities [Lopes and Oudeyer 2012; Bellemare et al. 2016; Burda et al. 2018; Colas et al. 2019; Lanier et al. 2019; Li et al. 2019; Akakzia et al. 2021]. Such agents usually use Automatic Curriculum Learning (ACL) methods, which rely on proxies such as learning progress or novelty to generate efficient learning curricula [Lopes and Oudeyer 2012; Bellemare et al. 2016; Burda et al. 2018; Colas et al. 2019; Akakzia et al. 2021]. Besides, other works train generative adversarial networks to produce goals of intermediate difficulty [Florensa et al. 2017], or use methods such as asymmetric self-play to train an adversarial goal generation policy with RL which samples interesting goals for the training agent [Sukhbaatar et al. 2017].

- Kaelbling, L.P. 1993. Learning to achieve goals. IJCAI, 1094–1099.

- Baranes, A. and Oudeyer, P.-Y. 2013. Active learning of inverse models with intrinsically motivated goal exploration in robots. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 61, 1, 49–73.

- Forestier, S. and Oudeyer, P.-Y. 2016. Modular active curiosity-driven discovery of tool use. 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), IEEE, 3965–3972.

- Schaul, T., Horgan, D., Gregor, K., and Silver, D. 2015. Universal Value Function Approximators. International Conference on Machine Learning, 1312–1320.

- Andrychowicz, M., Wolski, F., Ray, A., et al. 2017. Hindsight Experience Replay. arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.01495.

- Colas, C., Oudeyer, P.-Y., Sigaud, O., Fournier, P., and Chetouani, M. 2019. CURIOUS: Intrinsically Motivated Multi-Task, Multi-Goal Reinforcement Learning. International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 1331–1340.

- Akakzia, A., Colas, C., Oudeyer, P.-Y., Chetouani, M., and Sigaud, O. 2021. Grounding Language to Autonomously-Acquired Skills via Goal Generation. 9th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2021, Virtual Event, Austria, May 3-7, 2021, OpenReview.net.

- Forestier, S., Mollard, Y., and Oudeyer, P.-Y. 2017. Intrinsically Motivated Goal Exploration Processes with Automatic Curriculum Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1708.02190.

- Lanier, J.B., McAleer, S., and Baldi, P. 2019. Curiosity-Driven Multi-Criteria Hindsight Experience Replay. CoRR abs/1906.03710.

- Li, R., Jabri, A., Darrell, T., and Agrawal, P. 2019. Towards Practical Multi-Object Manipulation using Relational Reinforcement Learning. ArXiv preprint abs/1912.11032.

- Hermann, K.M., Hill, F., Green, S., et al. 2017. Grounded language learning in a simulated 3D world. arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.06551.

- Bahdanau, D., Hill, F., Leike, J., et al. 2018. Learning to understand goal specifications by modelling reward. arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.01946.

- Chan, H., Wu, Y., Kiros, J., Fidler, S., and Ba, J. 2019. ACTRCE: Augmenting Experience via Teacher’s Advice For Multi-Goal Reinforcement Learning. ArXiv preprint abs/1902.04546.

- Cideron, G., Seurin, M., Strub, F., and Pietquin, O. 2019. Self-Educated Language Agent With Hindsight Experience Replay For Instruction Following. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.09451.

- Jiang, Y., Gu, S.S., Murphy, K.P., and Finn, C. 2019. Language as an abstraction for hierarchical deep reinforcement learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 9414–9426.

- Fu, J., Korattikara, A., Levine, S., and Guadarrama, S. 2019. From language to goals: Inverse reinforcement learning for vision-based instruction following. arXiv preprint arXiv:1902.07742.

- Nair, A.V., Pong, V., Dalal, M., Bahl, S., Lin, S., and Levine, S. 2018. Visual reinforcement learning with imagined goals. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 9191–9200.

- Colas, C., Karch, T., Lair, N., et al. 2020. Language as a Cognitive Tool to Imagine Goals in Curiosity Driven Exploration. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, NeurIPS 2020, December 6-12, 2020, virtual.

- Akakzia, A. and Sigaud, O. 2022. Learning Object-Centered Autotelic Behaviors with Graph Neural Networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.05141.

- Warde-Farley, D., Wiele, T. Van de, Kulkarni, T., Ionescu, C., Hansen, S., and Mnih, V. 2018. Unsupervised control through non-parametric discriminative rewards. arXiv preprint arXiv:1811.11359.

- Mihaly, C. 2000. Beyond boredom and anxiety: experiencing flow in work and play. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Steels, L. 2004. The autotelic principle. In: Embodied artificial intelligence. Springer, 231–242.

- Colas, C., Karch, T., Moulin-Frier, C., and Oudeyer, P.-Y. 2022. Vygotskian Autotelic Artificial Intelligence: Language and Culture Internalization for Human-Like AI. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.01134.

- Eysenbach, B., Gupta, A., Ibarz, J., and Levine, S. 2018. Diversity is all you need: Learning skills without a reward function. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.06070.

- Pong, V.H., Dalal, M., Lin, S., Nair, A., Bahl, S., and Levine, S. 2019. Skew-fit: State-covering self-supervised reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1903.03698.

- Kingma, D.P., Welling, M., and others. 2019. An introduction to variational autoencoders. Foundations and Trends® in Machine Learning 12, 4, 307–392.

- Laversanne-Finot, A., Péré, A., and Oudeyer, P.-Y. 2018. Curiosity driven exploration of learned disentangled goal spaces. ArXiv preprint abs/1807.01521.

- Nair, A., Bahl, S., Khazatsky, A., Pong, V., Berseth, G., and Levine, S. 2019. Contextual Imagined Goals for Self-Supervised Robotic Learning. ArXiv preprint abs/1910.11670.

- Ecoffet, A., Huizinga, J., Lehman, J., Stanley, K.O., and Clune, J. 2019. Go-explore: a new approach for hard-exploration problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:1901.10995.

- Pitis, S., Chan, H., Zhao, S., Stadie, B., and Ba, J. 2020. Maximum entropy gain exploration for long horizon multi-goal reinforcement learning. International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, 7750–7761.

- Lopes, M. and Oudeyer, P.-Y. 2012. The strategic student approach for life-long exploration and learning. IEEE International Conference on Development and Learning and Epigenetic Robotics, IEEE, 1–8.

- Bellemare, M., Srinivasan, S., Ostrovski, G., Schaul, T., Saxton, D., and Munos, R. 2016. Unifying count-based exploration and intrinsic motivation. Advances in neural information processing systems 29, 1471–1479.

- Burda, Y., Edwards, H., Pathak, D., Storkey, A., Darrell, T., and Efros, A.A. 2018. Large-scale study of curiosity-driven learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1808.04355.

- Florensa, C., Held, D., Wulfmeier, M., Zhang, M., and Abbeel, P. 2017. Reverse curriculum generation for reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.05300.

- Sukhbaatar, S., Lin, Z., Kostrikov, I., Synnaeve, G., Szlam, A., and Fergus, R. 2017. Intrinsic motivation and automatic curricula via asymmetric self-play. arXiv preprint arXiv:1703.05407.

Comments