The Mandlerian Theory on Prelinguistic Concept Formation

Toddlers are the best learners we know to exist. From a very young age, they exhibit impressive behaviors when interacting with their surroundings. Interestingly, these capacities are not only dependent on caregivers, but can also come from autonomous interactions with objects. So how can an infant learn concepts on her own based only on sensorimotor interactions with the physical world ? On this matter, research has been mainly divided in two conceptually and factually different perspectives: the empiricist view, suggesting that knowledge comes primarily from sensory experience, and the nativist view, stating that certain skills and abilities are hard-wired into the brain at birth.

Many approaches in developmental psychology attempted to reconcile between the nativisit and the empiricist point of view by providing a minimal set of innate prerequired cognitive processing capabilities [Spelke 1994; Leslie 1994; Carey 2000; Leslie 2005; Carey 2009]. [Spelke 1994] proposes four innate modules to handle physics, psychology, geometry and reasoning about numbers. [Leslie 1994] suggests primitive modules that leverage causality, animacy and theory of mind. [Carey 2000] first emphasizes the need for two innate mechanisms to handle intuitive mechanics and intuitive intentional causality, and a third innate module is added in [Carey 2009] to handle the numerical cognitive system. However, all these works propose a rather static and domain-specific list of primitive capacities, which do not account for the flexibility of the continuous learning in children.

Recently, cognitive scientist Jean Mandler has proposed a new mechanism called Perceptual Meaning Analysis (PMA), which relies on a minimal collection of primitive core concepts embedded within infants [Mandler 2012]. The Mandlerian view recognizes the empiricist claim that concepts are learned during the humans’ lifetime, but argues that a minimal collection of primitives needs to be considered in order for this learning to kick off. The PMA mechanism transforms perceptual inputs into conceptual outputs, also known in the field of cognitive linguistics as image-schemas. The main difference that distinguishes PMA from earlier mechanisms is that it analyzes a few kinds of spatiotemporal information from a huge amount of information delivered by perceptual systems. This makes it a minimalistic and domain-general mechanism.

This blog post is organized as follows. First, we describe the theory of image-schemas from a developmental point of view. Then, we focus on the Mandlerian view on the subject and introduce the PMA mechanism. Finally, we argue that such a mechanism could be beneficial in artificial agents as it helps them categorize their sensory perceptions into semantic categories. Our goal is not to implement image-schema extractors nor PMA mechanisms, but rather to extract some concepts behind these developmental theories that can inspire and constrain our models of how agents may learn to represent their environment.

The Image Schema Theory

To understand the meaning of image-schemas, we propose to disentangle the two composing terms. We attempt to lay the background of our next parts by defining the following concepts from a cognitive linguistics point of view: a schema, an image, and image-schemas.

The Schema Theory

The term schema and its plural schemata have greek roots associated with the terms “form” or “figure”. In the late eighteenth century, Kantian philosophy was interested in schemas, and introduced them as means to relate percepts to concepts [Kant 1908]. More precisely, Kant starts from a known example to define a schema:

The empirical conception of a plate is homogeneous with the pure geometrical conception of a circle, in as much as the roundness which is cogitated in the former is intuited in the latter.

Kant considers a schema as a double-sided mediating representation, where one side is sensuous and the other is intellectual. These representations are fixed templates superimposed onto perceptions and conceptions to render meaningful representations.

Inspired by this philosophical point of view, cognitive science recently defined a schema as “a cognitive representation comprising a generalization over perceived similarities among instances of usage” [Kemmer and Barlow 2000]. This term was actually adopted decades earlier by the swiss psychologist Jean Piaget, who specically used the french term “schème” to design a framework used to make sense of raw perceptual information [Piaget 1923]. The main idea is that a schema defines a redescription of events (representation) that brings together in the same category the ones that share some common traits (similarities) to make behavioral generalization possible in humans. It can be viewed as a representation that allows humans to quickly organize new situations into categories without much effort. This organization, or schematic processing, starts at a very young age when toddlers first engage with their surroundings.

Mental Images

Humans have the capacity the continuously generate mental images of different concepts or events. This generation can be a recall from the memory of past experience, or an imaginary construction based on their understanding of certain concepts. The term image here should not be taken in its literal meaning. In fact, an image does not have to be exclusively visual, but can involve a perceptual collection of auditory, haptic, motoric, olfactory and gustatory experiences [Oakley 2007]. In any case, images are necessarily grounded in perception, providing abstractions on which an individual could eventually add building blocks to frame new experiences. Let’s try to better understand the concept of image with an example. Let’s consider a detailed mental image of a pile of clothes that you may have left on your bed one morning when you were rushing out to work. This image is \textit{specific} to those particular objects (clothes) and not to any other ones. Although this experience involves a particular set of objects, it still serves as an imaginative base for creating a schematized mental image of a stack of any other types of objects. In other words, the image is specific, but can be used with some other component to generalize the concept it represents.

Image-Schemas

It was initially the field of contemporary cognitive linguistics that got interested in combining the notions of schema and image [Arnheim 1997; Johnson 2013; Oakley 2007]. Image-schemas can be viewed as mental images of abstract context-agnostic concepts. Thus, unlike an image, an image-schema is not specific nor fixed as it represents highly preconceptual and primitive patterns that enable reasoning in many contexts. To better understand the nuance, we consider the following example. Think of a blue lego brick being put on a red lego brick. This is an image: it is specific and fixed. The underlying image-schema can be the OBJECT ON OBJECT: it is not specific and not fixed. Hence, we are able to construct flexible and abstract representations from specific images. Other examples of image-schemas PATH-GOAL, ATTRACTION, CENTER, PERIPHERY and LINK [Geeraerts 2006].

Most works in cognitive linguistics followed the Piagetian behaviorism point of view suggesting that concept formation in infants does not happen until language is acquired [Bogartz et al. 1997; Haith and Benson 1998; Sloutsky 2010]. However, decades of investigations on preverbal infant cognition emphasized the role of prelinguistic conceptualization in understanding the world [Leslie 1994; Spelke 1994; Mandler 1999; Mandler 2012]. Notably, some of these works suggest that language comes later as an enrichment to these prelinguistic conceptualization, rather than being a prerequisite [Mandler 2012; Mandler and Cánovas 2014]. Interestingly, the same works argue that these prelinguistic image-schemas are strictly spatial, allowing preverbal toddlers to build their foundational conceptualization capacities by mapping spatial structure into conceptual structure [Mandler and Cánovas 2014]. The process of formation of these image-schemas depends on some innate perceptual information responsible for monitoring toddlers attentions, as shown in experiments with 2 and 3 months children [Baillargeon 1986; Hespos and Baillargeon 2001]. Recently, a mechanism was proposed to describe the preverbal formation of spatial image-scheme: the Perceptual Meaning Analysis mechanism (PMA) [Mandler 2012].

The Perceptual Meaning Analysis Mechanism

The Perceptual Meaning Analysis (PMA) [Mandler 2012] is a general framework that accounts for the conceptual activity in the first years of life. It attempts to reconcile between the empiricist and the nativist views. On the one hand, the PMA mechanism recognizes that the concept formation in infants is learned, thus accounting for the empricist view. On the other hand, it argues that in order for this learning to kick off, a minimalist set of primitives need to be considered. In this part, we introduce three main properties of the PMA mechanism which are not leveraged by earlier approaches, thus making it more promising to handle prelinguistic concept formation in infants.

PMA translates Temporal Information into an Iconic Spatial Form

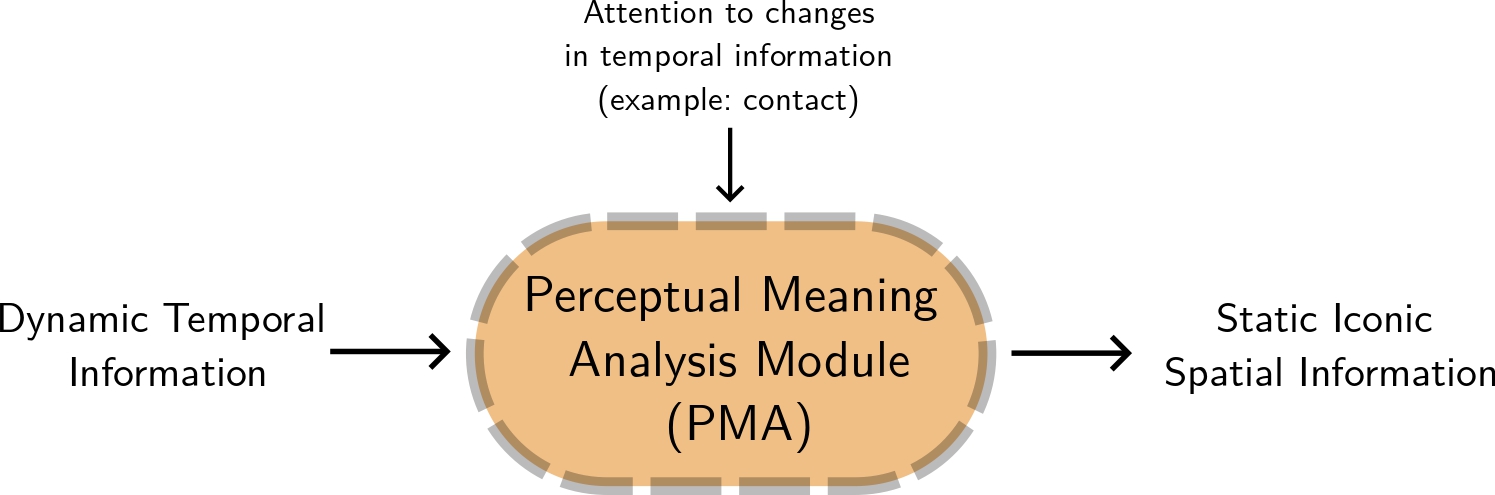

In the introduction to this blog post, we highlighted that PMA considers only a set of primitives. A fair question arises: what exactly are these primitives, and how do they make PMA more promising than other approaches? The theory of prelinguistic concept formation established by PMA suggests that perception-based representation learning is based on attended information. In fact, it starts the conceptual system by directing the attention of infants to things moving on paths through space [Mandler 2012]. A toddler sees for example the hand of her caregiver moving to grasp a toy. It is at the moment of touching the toy (establishing the ``LINK” as described by Mandler [Mandler 2012]) that the attention of the toddler gets focused on the specific perception of a hand touching an object. PMA translates this temporal information (hand moving towards the toy) to iconic spatial form (hand far from toy, hand in contact with the toy). Based on these thoughts, what is actually innate within infants is the attention capacity towards temporal changes, allowing them to distinguish different situations based on the contact. That is why the earliest concepts learned correspond to spatial relations [Mandler 2012]. Compared to earlier approaches, PMA provides a domain-general mechanism, as infants may learn concepts in one situation (the example of the caregiver reaching the toy), and generalize it to any other situation including a physical contact between two objects. Figure 1 illustrates the idea behind the PMA module.

Fig.1 - Illustration of the PMA module. It takes as input temporal information and translates it into iconic spatial static form. It only requires attention to temporal physical changes.

Language supports PMA’s Enrichment

The PMA mechanism comes with a minimalistic collection of primitives that allow the acquisition of spatial image-schemas. However, PMA continues to develop as the infant grows up. Namely, the social situatedness that characterizes the early life of toddlers clearly affects their perceptual analysis. In particular, their confrontation to language, as they hear their caregivers engaging with them, unleashes a growing repertoire of new conceptualizations.

On the one hand, language enables the subdivision of global concepts. In fact, caregivers provide language descriptions of animate or inanimate objects which direct the toddlers’ attention towards features that were originally neglected within their autonomously generated image-schemas. Experiences with 6 months infants show that they begin to use labels provided by adults to subdivide animals [Fulkerson and Waxman 2007]. Although the child may be globally familiar with a concept, the consistent use of language-based distinctions from adults further directs the child’s attentive analysis, enabling the discovery of novel properties that were originally overlooked.

On the other hand, language promotes the expansion of the conceptual system beyond spatial information. Recall that the PMA mechanism is initially strictly spatial. In fact, the PMA mechanism deals better with spatial perceptual information because they are usually structured. However, more unstructured sensory information such as colors, tastes and emotions have no primitives within the PMA mechanism. Although infants experience these unstructured information, there is no evidence, to my knowledge, for their conceptualization before language. Language labels provided by adults provide a symbolic system enabling children to map the unstructured perceived information to discrete categories.

PMA supports Language Learning

Infants come to the language learning task with a set of image-schemas translating their understanding on abstract concepts involving spatial primitives. Interestingly, grammatical relations within language are also abstract, which suggests that these same image-schemas could also play an important role in providing the relational notions that structure sentences. In fact, research on early language acquisition shows that children rely on notions that can be described in image-schema terms [Tomasello 1992]. More importantly, the first explicit grammatical particles that appear in English-speaking toddlers are mainly prepositions such as in and on which respectively express containment and support. This perfectly fits with the idea that prelinguistic image-schemas which mainly involve spatial concepts support early language learning. To further reinforce this claim, researchers were interested in other languages that, unlike English, are not prepositional. For instance, some experiences involved Korean, within which containment and support are rather expressed by verbs translating a degree of fitness [Choi et al. 1999; McDonough et al. 2003]. The results showed that Korean infants too begin to acquire the common spatial morphemes of their language at the same age as English infants.

The claim that image-schemas support learning of languages such as English and Korean is possible because studies with these particular languages show that infants tend to first acquire spatial words (prepositions or verbs describing spatial relations). However, the existing variety of human languages makes the generalization of this claim somehow unsupported. In any case, I do not think that image-schemas are necessarily a prerequisite for language learning, even though they might potentially facilitate it.

Artificial Intelligence and Perceptual Meaning Analysis

The field of Artificial Intelligence (AI) confronts two opposing currents: connectionist AI that aims to learn as much as possible from data in an end-to-end fashion; symbolic AI which implements inductive biases and several hand-coded symbolic modules. This opposition is analogous to the one between empiricism and nativism described throughout this blog post (where empiricism is close to connectionist AI and nativism to symbolic AI). We align with the variety of research believing that these two currents are actually complementary. Recently, research has been investigating the middle grounding between symbolic AI and connectionist AI by incorporating symbolic representations within end-to-end computation tools such as neural networks. These approaches, called neuro-symbolic AI, are shown to be successful in many domains such as control [León et al. 2020], visual question answering [Andreas et al. 2016; Zhu et al. 2020] and theorem proving [Minervini et al. 2018].

As PMA describes a model for prelinguistic concept formation in infants, endowing artificial agents with a similar mechanism seems promising. More specifically, embodied artificial agents that are endowed with raw sensors might make use of a conceptual PMA-like mechanism. Such agents would be able not only to perceive their world as it is, but to build concepts and categorizations based on spatial relations. In Figure 2, we illustrate the potential capabilities of PMA-based agents compared with standard ones. PMA-based agents would in principle be able to categorize their sensory perceptions into semantic categories based on the underlying semantic features. This might facilitate skill acquisition, facilitate language grounding and increase behavioral diversity.

Fig.2 - Embodied Artificial Agents with and without PMA module.

- Spelke, E. 1994. Initial knowledge: Six suggestions. Cognition 50, 1-3, 431–445.

- Leslie, A.M. 1994. ToMM, ToBy, and Agency: Core architecture and domain specificity. Mapping the mind: Domain specificity in cognition and culture 29, 119–48.

- Carey, S. 2000. The origin of concepts. Journal of Cognition and Development 1, 1, 37–41.

- Leslie, A.M. 2005. Developmental parallels in understanding minds and bodies. Trends in cognitive sciences 9, 10, 459–462.

- Carey, S. 2009. Where our number concepts come from. The Journal of philosophy 106, 4, 220.

- Mandler, J.M. 2012. On the spatial foundations of the conceptual system and its enrichment. Cognitive science 36, 3, 421–451.

- Kant, I. 1908. Critique of pure reason. 1781. Modern Classical Philosophers, Cambridge, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 370–456.

- Kemmer, S. and Barlow, M. 2000. Introduction: A usage-based conception of language. Usage-based models of language, 7–28.

- Piaget, J. 1923. Le langage et la pensée chez l’enfant. Delachaux and Niestlé.

- Oakley, T. 2007. Image schemas. The Oxford handbook of cognitive linguistics, 214–235.

- Arnheim, R. 1997. Visual thinking. Univ of California Press.

- Johnson, M. 2013. The body in the mind: The bodily basis of meaning, imagination, and reason. University of Chicago press.

- Geeraerts, D. 2006. Cognitive linguistics: Basic readings. Walter de Gruyter.

- Bogartz, R.S., Shinskey, J.L., and Speaker, C.J. 1997. Interpreting infant looking: The event set\times event set design. Developmental psychology 33, 3, 408.

- Haith, M.M. and Benson, J.B. 1998. Infant cognition. None.

- Sloutsky, V.M. 2010. From perceptual categories to concepts: What develops? Cognitive science 34, 7, 1244–1286.

- Mandler, J.M. 1999. Preverbal Representation and Language. Language and space, 365.

- Mandler, J.M. and Cánovas, C.P. 2014. On defining image schemas. Language and cognition 6, 4, 510–532.

- Baillargeon, R. 1986. Representing the existence and the location of hidden objects: Object permanence in 6-and 8-month-old infants. Cognition 23, 1, 21–41.

- Hespos, S.J. and Baillargeon, R. 2001. Reasoning about containment events in very young infants. Cognition 78, 3, 207–245.

- Fulkerson, A.L. and Waxman, S.R. 2007. Words (but not tones) facilitate object categorization: Evidence from 6-and 12-month-olds. Cognition 105, 1, 218–228.

- Choi, S., McDonough, L., Bowerman, M., and Mandler, J.M. 1999. Early sensitivity to language-specific spatial categories in English and Korean. Cognitive Development 14, 2, 241–268.

- McDonough, L., Choi, S., and Mandler, J.M. 2003. Understanding spatial relations: Flexible infants, lexical adults. Cognitive psychology 46, 3, 229–259.

- León, B.G., Shanahan, M., and Belardinelli, F. 2020. Systematic generalisation through task temporal logic and deep reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.08767.

- Andreas, J., Rohrbach, M., Darrell, T., and Klein, D. 2016. Learning to compose neural networks for question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:1601.01705.

- Zhu, X., Mao, Z., Liu, C., Zhang, P., Wang, B., and Zhang, Y. 2020. Overcoming language priors with self-supervised learning for visual question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.11528.

- Minervini, P., Bosnjak, M., Rocktäschel, T., and Riedel, S. 2018. Towards neural theorem proving at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:1807.08204.

Comments